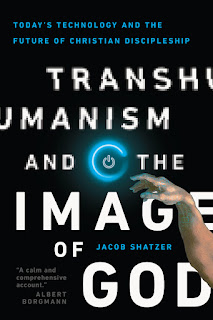

"Transhumanism and the Image of God" by Jacob Shatzer. A Book Review

Transhumanism and the Image of God: Today's

Technology and the Future of Christian Discipleship

Jacob Shatzer

IVP Academic

InterVarsity

Press

PO Box 1400

Downers Grove, IL 60515

PO Box 1400

Downers Grove, IL 60515

ivpress.com

ISBN: 978-0-8308-5250-5;

April 2019; $22.00

5 Stars of 5

With the

growing matrix of social media, artificial intelligence, robotics, and prosthetic

enhancements, people should be asking all types of questions. And they are,

just not always the right ones. Some are asking “What more can be done?” while

others are inquiring “What should be done?” Jacob Shatzer, assistant professor

and associate dean in the School of Theology and Missions at Union

University, ordained Southern Baptist minister and author, addresses more of

the “What is going on, why, and how are we to rightly engage?” queries in his

new 192 page softback: “Transhumanism and the Image of God: Today's

Technology and the Future of Christian Discipleship.” Shatzer focuses on technological advances, the thinking going on

among transhumanists and posthumanists, and searches out ways for Christians to

decrypt the ought from the is. He writes for a broad spectrum of interested

people, and those who should be interested.

The main concept running through “Transhumanism and

the Image of God” is that we humans make tools, and then tools make us. We

construct technological tackling and it in turn molds our perceptions and

directions. Which means that technologies are “shaping us. And shaping people,

after all, is just another way of talking about discipleship” (8). Therefore,

“part of responsible, wise, faithful use of tools is analyzing the ways that

certain tools shape us to see the world in certain ways, and then to ask whether

those ways are consistent with the life of a disciple of Christ” (7). Thus, the

author argues “that Christians must engage today’s technology creatively and

critically in order to counter the ways technologies tend toward a transhuman

future…Human making is happening, and technology is a powerful part of that

making, sneaking its values into us at almost every turn” (11).

The first half of the book pointedly examines the

issue. In these first five chapters the author explains what transhumanism is and

how it undergirds a posthumanist aim. He unpacks the various pedigrees and personalities

that formed transhumanism and where they are (from Google to Facebook and

beyond). He looks into several of their tenets, where they are beneficial and

how they are problematic. Shatzer also attends to the transhumanist notion of

morphological freedom, which “means the ability to take advantage of whatever

technology a person wants to in order to change their body in any way they

desire” (56). This momentum continues, progressing to the place where the human

and machine merge bringing humans to augmented reality as well as to potential

mind clones.

The author perceives that many of these aspects are

already in their early stages, and we are unthoughtfully employing them from

our smartphones to our newest cutting-edge gadgets. Therefore, Shatzer

helpfully works through each item, and after explaining them and their advantageous

uses, thoughtfully works around how we should think about these advances and

changes, and where we should go; “If we want technology to serve the community,

then, it must be useful to move people toward the ultimate good not defined by

technology itself” (35). He further moves, in the last five chapter, to guiding

the reader to a more critical position by asking important questions, such as

what is real, where is real, who is real, and am I real? I appreciated how the

author exposes the clearly gnostic underpinnings that flow through our

technological advances – the desire to transcend the body because it is

expendable – and he grounds our rightful concerns and corrections in the

incarnation: “The doctrine of the incarnation shows us why full, embodied

humanity is the goal, and the importance of this doctrine warns us of danger in

embracing a version of humanity that rejects “in the body.” Jesus’ physical

presence is foundational” (122). The book, and especially the concluding

chapter, offers multiple suggestions on ways to manage technological uses in a

reader’s life.

“Transhumanism and the Image of God” is neither

shrill nor panic-stricken. The author helps the readers to keep their heads

about them while seriously engaging technology, transhumanists and

posthumanism. Clear and comprehensible, Shatzer makes a solid case, and gives sound

counsel. This volume is ideal for Christians involved with IT (which is almost

everyone I know!). If you have a smartphone, iphone, android, ipad, laptop, tablet,

etc. you should pick up a copy and make it a reading priority. I highly

recommend this book.

My thanks to IVP Academic for sending, at my

request, a copy of the book used for this review. They asked nothing in

exchange other than my honest opinion. And so all of the thoughts and remarks

are mine, freely given and freely bestowed.

Comments